Truth, Edited

Working at CNN, the Stories We Told Ourselves and the Public

I was working at CNN in the early eighties — a videotape editor mostly, sometimes filling in as a field photographer when they needed an extra set of hands. I was still new. Still wide-eyed enough to think the news was mostly about the truth.

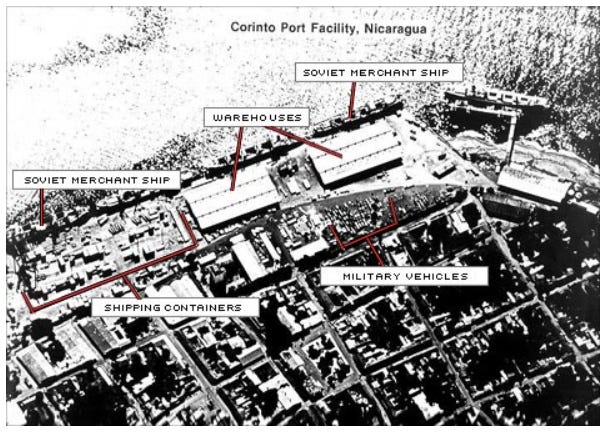

One of my early trips was to Nicaragua with a CNN reporter — a Canadian, tall, chain-smoker, blond hair parted in the middle. He’d been covering El Salvador and got sent to Nicaragua when word came through that an Eastern Bloc cargo ship was headed toward the coast. The CIA said it was carrying weapons. Soviet stuff. Helicopters maybe. It was late 1984, back when everything in Central America looked like a proxy war waiting to happen. So CNN flew us down from Atlanta.

We got to Managua in the middle of the day, just a few hours before sunset. I remember the air — thick, dusty, and heavy with diesel. The government at the time was Sandinista, led by Daniel Ortega. They had maybe a dozen tanks in the whole country. They parked them in visible places — intersections, fields, sometimes in front of government buildings — to make it look like strength. Kids were climbing on them like playgrounds. It wasn’t a show of force. It was a show. Period.

We shot what we could — some wide angles, some of the tanks, a few quick takes of the coastline. CNN wanted something fast. “Get a phoner,” the desk said. That meant Leigh would call in from a landline, do a live audio interview while the anchors back in Atlanta filled the screen with his still photo. So we found a little phone center — a handful of booths, pay-by-the-minute. I sat outside with our camera operator, Maria, and a Dutch journalist who was waiting her turn.

Leigh got patched through to Atlanta. We could hear every word from outside the booth. And that’s when he started describing the “troops flooding the streets” and “tanks positioned across the city.” The camera woman and I looked at each other. The Dutch reporter raised her eyebrows and asked who he was. We told her quietly, embarrassed — “CNN.”

In reality, the streets were calm. The tanks were rusting props. The only thing moving fast was the humidity. But that’s not what people saw when they turned on the news that night. They heard a correspondent in Managua describing tension and troop buildup. They saw graphics. They heard experts in Washington speculating about Soviet arms and CIA sources and “regional instability.” And just like that, the story had a life.

When Leigh hung up, he walked out smiling. He didn’t mean harm — he was doing his job, painting a vivid picture, selling urgency. We packed up and went back to the hotel. But I never forgot that moment — the sound of someone describing a reality that wasn’t quite there, and the quiet we sat in afterward.

That wasn’t the only time. Later, when I was back in Atlanta editing tape, I caught myself doing the same thing — framing shots tighter, cutting sequences to make small protests look larger, slicing chaos into rhythm. Not to lie. Just to make it play.

It wasn’t malicious. It was craft. But sometimes craft turns into distortion, and you don’t even notice.

I remember the Marine Barracks bombing in Beirut, October 23, 1983. Two hundred forty-one U.S. service members were killed — Marines, Navy, Army — most of them asleep in their bunks when a truck full of explosives hit the building.

We had footage, raw and violent. Too violent. CNN made the decision — and I agreed at the time — not to show the worst of it. But I’ve questioned that choice ever since.

Maybe people should have seen it. Maybe hiding the blood made it easier to move on, easier to let it fade into the next story.

Maybe truth isn’t just what you say — maybe it’s what you refuse to show.

These days, it’s not just networks doing it. Everyone with a phone can be a broadcaster. YouTube. TikTok. Independent “journalists” chasing clicks and outrage.

And just like before, the angles are tight. You see twenty seconds of someone screaming, not the hour that came before. You see the tanks, not the kids climbing them. It’s the same trick, just smaller cameras.

I don’t think it’s all the media’s fault. We get the news we’re willing to watch.

Most people don’t want nuance; they want confirmation. They tune in to hear what they already believe — Fox, MSNBC, whatever fits. And the cycle keeps spinning. Truth gets trimmed to fit the frame.

I don’t know if any outlet is truly neutral anymore.

The Christian Science Monitor used to be close — slower, quieter, almost allergic to hype. Maybe we could use more of that now. But maybe the real problem isn’t the networks at all. Maybe it’s that we’ve forgotten how to think critically, how to look past the cut.

I still think about that day in Nicaragua.

The phone booth. The echo of the reporter’s voice carried out into the hallway.

The Dutch reporter’s face.

The sound of the tanks that weren’t moving.

And the real and only truth that never made it on air.